Human beings live and work in groups. Each group develops characteristic behaviour patterns based on implicit theories, which become in time, ‘traditions’ that future generations are exhorted to follow. Differences arise between groups based on race, ethnicity, religion and so on.

Still, on looking closely, one might find that people across the globe are more similar than different, because of similar operative concepts, especially on the gender question. These can transform with new reality, but the basic threads of the ideology, the gender-role belief systems “rooted in the structural relationship between the two sexes” resist change.

The traditions grow out of a continuum of positive and negative behaviours. Traditional masculinity, for instance, is associated with: personal sacrifice for dependents and calmness in danger. But it is also associated with: coercive behaviour, date-rape attitudes, high-risk behaviour and unemotionality. Thence ‘maleness’ finds expression in a collection of behaviours adapted to the needs of the specific cultural group.

A study in USA on the differential patterns identifies 5 endorsements types of the masculine ideology:

· traditional

· high violence/moderately traditional

· moderately traditional

· high status /low violence

· non-traditional

These five endorsements were then related to the men’s gender-role beliefs in terms of:

· Status/rationality

· Anti-femininity

· Tough image

· Violent toughness

· Gender-role egalitarianism

In the study, the non-traditional group of men was found less overtly masculine. They scored lower in the four variables of status, image, violence, and anti-femininity and higher than the rest in gender-role egalitarianism.

Each of the other masculine clusters identified – traditional, moderately traditional, high violence/moderately traditional and high status/low violence - were found to be moderate to high on ‘tough image’, ‘status’, and ‘anti-femininity’. To these groups, the presentation of an appropriate public image was the point.

Fischer and Good write:

… being perceived by others as tough, self-sufficient, and confident was at least moderately important… as a “ritualized form of masculinity that entails behaviors, scripts, physical posturing, impression management, and carefully crafted performances that deliver a single, critical message: pride, strength, and control…

However, a difference was perceived in the mix regarding “violent toughness”. As the researchers explain their findings:

… men in both the High Violence/Moderately Traditional and Traditional clusters reported relatively strong endorsement of Violent Toughness as part of their masculinity ideologies … men who endorsed rather traditional-to-moderate beliefs regarding Status/Rationality, Antifemininity, and Tough Image also held quite nontraditional beliefs regarding Violent Toughness as important to masculinity (i.e., those in the High Status/Low Violence cluster).

In other words, they are divided on the display of machismo. Some wear the badge of violence; others emulate the minority ‘non-traditional’ group. Why the change? Considering their strong ‘anti-femininity’ responses, that ‘low violence’ men could be distancing altogether from gender domination and control is in doubt. Perhaps this group of status-seekers make tactical changes in the gender interface for impression management!

In many modern dual-income families, men may be uncomfortable with their wives choosing career development over part time jobs. Despite education and economics, the masculine devaluation and distrust of women is universally ingrained. At home and at work, women’s advancement may pose threats to their individual high status. In India, for instance, divorce rates and single-mother-households are both on the rise.

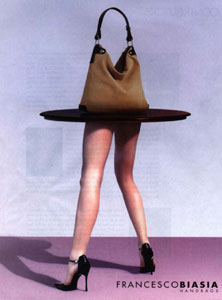

Now, the high status/low violence group may be eschewing physical violence only to project in public the egalitarian image. To keep the progressives from unsettling the status quo, the subtle mode of gender discriminations may be applied instead, like objectification. Men of all cultures may ensure this feminine preoccupation with body issues with constant social reinforcements of the ‘standards’ to be achieved for their acceptance.

Now, the high status/low violence group may be eschewing physical violence only to project in public the egalitarian image. To keep the progressives from unsettling the status quo, the subtle mode of gender discriminations may be applied instead, like objectification. Men of all cultures may ensure this feminine preoccupation with body issues with constant social reinforcements of the ‘standards’ to be achieved for their acceptance.

What about the feminine ideology? In the patriarchal social structure, gender inequality is built in. “Female domesticity “ has been idealized throughout its history. Following the social learning in “subordination”, women eventually collaborate with men to carry forward the inequality.

Jackson opinions that:

…women accepted male power outside the household in return for "rule in their own place."… they received "secondary gains" of social status, leisure, freedom from responsibility to earn an income, and the freedom "to devote a major portion of her time to personal adornment and attention to herself" through marriage.

In the last two centuries of organized social life, any change in women’s status has revolved around the basic tenet. More recent economic, political and legislative changes attempt to counter women’s subordination and gender inequality. But the outlook that arose from implicit beliefs and practices of male supremacy is yet to be eradicated worldwide.

Social norms targeting women cut across the divides of culture and race. For instance, women in Asia and Africa have over centuries, suffered torture to meet ‘standards’ of traditional beauty and sexuality. In the Asian Far East, the feet of female children were bound from birth to keep them small. On the African continent, young girls were forced to undergo genital mutilations to be acceptable for marriage.

Impett et al write:

Girls experience immense pressures to behave in feminine ways, both in their relationships with other people (i.e., by suppressing their own authentic thoughts and feelings) and in their relationships with their own bodies (i.e., by suppressing bodily hungers and desires to conform to prevailing images of beauty and attractiveness).

The objectification theory Fredrickson & Roberts formulated in 1997, suggests that women tend to internalize the socio-cultural values and “become their own first surveyors”. Researchers say:

… women learn to view themselves primarily through an observer’s perspective. According to objectification theory, society places more emphasis on attractiveness for women than men, such that women are constantly subject to appraisal of their appearance. Sexual objectification occurs when a person is treated as a body valued for its use by others.

Women have been taught over the ages that their personal sense of self and value in personhood rests almost entirely on others, especially the male gender, responding positively to their appearance – size, shape, colour, dress and what-have-you.

…educational level, occupational level, and family income each were stratified by skin tone; higher mean educational attainment, greater participation in professional and technical careers, and higher income were associated with lighter skin tone.

In India, fairness of skin, a legacy of cultural invasions, has long been an index of beauty in the country. Fairness creams are the fastest moving consumer goods for women and men. Product advertisements suggesting associations between skin colour and upward mobility thus blatantly fill corporate coffers.

Buchanan et al write that:

Theoretically, this continual evaluation of the self in terms of internalized societal ideals may result in negative psychological consequences such as increased shame and anxiety. These psychological consequences of self-objectification may lead, in turn, to increased risks for mental health concerns such as depression, eating disorders, and sexual dysfunction.

Women in India and elsewhere, of the educated and employed circles as well, do little to improve their objectified status, and their debased self-esteem. The social learning has been to avoid conflict; hence the idea of confrontation is itself too stressful to contemplate.

They would prefer to tune out of their present unequal circumstances, immerse in serialized soap operas suspending judgement and reflection on their subtle sexist messaging, or even fantasize that in individual suffering they contribute to the greater good. Implicit theories of gender inequality continue to flourish because women are yet to unite voices against second-class citizenship.

References for this post:

- Bidisha “Pubic hair removal: The naked truth” Article guardian.co.uk The Guardian, Friday 11 February 2011 http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2011/feb/11/womens-pubic-hair-removal-porn

2. Buchanan, Taneisha S. Fischer, Ann R. Tokar, David M. and Yoder, Janice D. “Testing a Culture-Specific Extension of Objectification Theory Regarding African American Women's Body Image” The Counseling Psychologist Volume 36 Number 5, September 2008 697-718 originally published online 8 July 2008.

- Fischer, Ann R. and Glenn, E. Good. “New Directions for the Study of Gender Role Attitudes: A Cluster Analytic Investigation of Masculinity Ideologies”. Psychology of Women Quarterly 22 (1998), 371-384

- Impett, Emily A, Schooler, Deborah, Tolman, Deborah L. “To Be Seen and Not Heard: Femininity Ideology and Adolescent Girls’ Sexual Health”. ARCHIVES OF SEXUAL BEHAVIOUR, Volume 35, Number 2, 129-142.

- Jackson, Robert Max “Chapter 8. Disputed Ideals: Ideologies of Domesticity and Feminist Rebellion” nyu.edu Working Draft of DOWN SO LONG . . . Undated.