Maslow’s theory places needs in a hierarchy, postulating that higher needs emerge on fulfillment of lower ones. On satisfaction of physiological needs, new needs for security emerge in people’s minds. When security has been dealt with, social needs have to be met; after which, self-esteem become potent. Thereafter, the self-actualizing needs begin to arise. The common assumption grows that as long as lower needs are unfulfilled, higher needs are dormant. By extension, since those surrounded by poverty must barely meet their physiological needs, they must aspire no further.

We decide to visit a rural district in West Bengal, a few hundred miles out of Kolkata to find out. Our city acquaintances enumerate the tourist spots of the region for us – religious icons and cottage industry. We are told where we can absorb the spirituality, and also where items for our drawing rooms would come cheap. The blanket assumption seems to be that the faceless masses have no talents otherwise to positively contribute to society. In fact, in remote pockets of the country, the backwardness of indigenous communities and tribes are kept as such in practices meant to preserve ancient cultures. These populations remain in isolation on reservations cut off from the mainstream, attractions for avid tourists and anthropologists. Small wonder then, that in carrying forward the traditions of the ages, their associated superstitions are also swallowed unquestioningly.

Meanwhile, technological advancements have concentrated in the metros, where competitions of the global marketplace are generally intellect-based. Although the urban numbers are but a fraction of India’s vast population, manpower supply exceeds demand. The prices of skills drive down, which is the basis of the lucrative outsourcing industry. A surfeit of Indian men and women join the virtual reality of business and knowledge processes. They change names and accents to handle services informatics for Western consumers, beaming out advice from a nation devoid of the same organized social system.

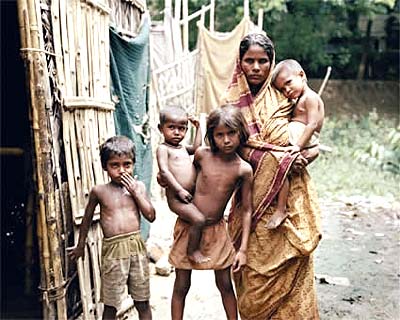

At least 25% of India lives below the poverty line mainly in the far-flung regions, where daily subsistence is a challenge. There is a label for this category of people – bpl, i.e., incomes of less than half of one US dollar a day. And ‘they’ are not just individuals, but extended families made up of parents, grandparents and children, dependent on local vegetation and governmental subsidies to survive in the age of information.

Beyond city limits, the surroundings change. There are more open spaces of natural beauty, and more greenery lining the highway, the tree branches meeting overhead to form a natural canopy. Breathing is automatically easier as pollutions of the concrete jungle are left behind, and we pass open fields of agricultural crop and fruit orchards. But the living standards are impoverished, small dwellings tinged with neglect and the sense of time standing still, cheek by jowl with large tracts of land acquired for development by corporate houses, walled off from the humble populace.

At our destination, it is a surprise to actually see a building made of brick and mortar, three storeys high, with further work in progress. We hear that outlying institutions receive governmental grants for building structure, although they must find the funds elsewhere to actually run the school. The institution, for boys only, boasts of eleven hundred names on the rolls, but privately we learn that keeping children in school is their greatest problem. A free mid-day meal is an incentive, but in middle school between classes VI-VIII, attrition is high.

The village boys are expected to follow in the footsteps of their forefathers, preserving occupational traditions. For many of the parents, modern education is a waste of time, and there is more economic worth in an extra pair of hands at work. In much of rural India, even males seeking academic achievements, are in minority. And women, far less able to cross the gender boundaries of the ages, scarcely enter the equation.

Eleven teachers deal with the inmate population of the school, at a ratio of 1:100, with less than half a minute to spare for each individual in class. In educational infrastructure there is but one computer to look at but not touch, one rack of books in the ‘library’, and students are yet to practice using dictionary and thesaurus. The school management we meet is ambitious; their goal is the recognition and grants of higher secondary status. That calls for results in Board examinations. The institutional targets push the faculty to contribute personal resources to provide free books, school uniforms and coaching after-hours to achieve exam readiness in their pupils.

We ask the school authorities for student background information. We learn that the general occupations of the region are: business, farming, small service, cultivation, labour, and labour (bpl). Although the actual economic value of each of these jobs may vary in comparison to the city, it seems safe to assume that “business” and “labour (bpl)” are at the two ends of the economic spectrum, with the former at a higher standard of living, the latter unable to make ends meet.

It seems logical to assume that students’ academic performances link with their economic backgrounds. Indeed, the “business” children do average scores higher than the “labour (bpl)” boys - by about 10-15 percent marks in summative exams. But surprisingly, scions of “small service” that middle the economic ladder, lead both, scoring marks in the ninety percents. So the correlations perceived are incidental, not cause and effect.

A theory builds from studies that control or balance interfering variables. Extrapolations from it make sense if the contexts are the same, else they hardly fit. When the guiding influences on people's lives have diverse sources, or the environment itself is in turmoil, the emergence of new needs may depend instead on intrinsic motivations generated from individual social learning. The dominance or subordination of a particular need is therefore more random and unpredictable than theoretically assumed.

Blessed with fertile lands and climes, India has largely been agrarian over the 5 millennia of its civilization. Rural cultures continue to steep in the ways things have always been and carry on the customs and rituals of ages gone by, juxtaposing ancient worship of the sylvan goddess with overlays of male dominance. They live in closed communities whose leaders assume extra-constitutional authority over their life choices. The political exploitation of this power over people ensures that any form of modernity is slow to arrive among the silent majority, the apparent drag to India’s economic ascendancy in the new millennium.

The changes imposed on the ordinary people of India over the last six decades of independence have been immense: colonial to democratic, agrarian to industrial, joint to nuclear family structure, and manual labour to electronic wizardry among others. In India’s collectivistic society, vacillations continue between traditions and modernity. The Diva writes elsewhere that:

The forces pulling physically and spiritually one way and politically and intellectually another, generate conflicts and tensions over cultural and material issues.

The condition is termed Trishanku in Indian parlance after the mythological king who, in attempting to take his mortal body to heaven, remains suspended in ether for evermore, neither here nor there.

The backwardness of people groups may be a state of mind, a failure of imaginative perceptions and opportunity perhaps, rather than some genetic anomaly. The home environs provide children with purpose in life in formative years. Parents and elders passing on perspectives of the world, attach value to education. For instance, the “business” person, hierarchically at the top of his little organizational pyramid, socializes attitudes and ethics that may differ from one in “small service”. The latter, on the bottom rung in a larger system, is like a small fish in a large pond, and must develop skills to be aware of others, learn diverse survival skills and adapt to changing influences. The outlook to education may hence differ in business, small service and other families.

Often in India, talent is thus suppressed, lost to the nation and humanity, because of faulty perceptions within and between social groups. Rural people are not mentally retarded but de-motivated by lacks of opportunity and resource. Doles are hardly the remedy. Rather, they need educational support to realize their worth, and shine in the larger world of people. The talent to self-actualize exists in people everywhere, whether it is the aptitude to excel in a certain field or discipline, or the ability to rise above average natural ability through sheer diligence; it just needs a trigger to thrive.

Governance still struggles to create the infrastructure for organized social services as in the West; hence in people development, they can do little beyond building a few school structures. It behooves individuals and corporate bodies that are more privileged, to acknowledge the social and gender inequality, engage in citizenship to replenish the macro community and bring worth to minority groups. Perceiving India’s vast underprivileged population as talent under the radar rather than a drag is the first step forward in fulfilling the collective social responsibility.